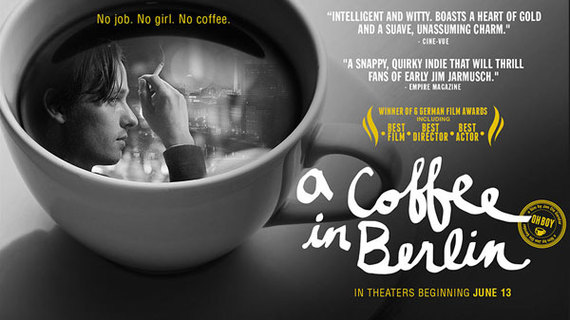

Niko Fischer (Tom Schilling) in A Coffee in Berlin, courtesy of Music Box Films

Twenty-something ennui (aka “the slacker”) is not endemic to the United States, as evidenced by German director Jan Ole Gerster‘s debut feature, A Coffee in Berlin. The film—which swept the German Film Academy Awards—follows a day in the life of Niko Fischer (Tom Schilling, The Baader-Meinhof Complex), a law-school dropout who can’t seem to get a handle on who he is and where he’s heading. Niko can’t commit to his girlfriend, he’s a major disappointment to his successful father, and he can’t even scrape up a decent cup of coffee.

In the vein of Woody Allen, Richard Linklater and other astute observers of the mundane and the absurd, Gerster paints a distinct portrait of a snapshot in time, in a specific location, while still making the story seem universal. Haven’t we all felt like Niko at some point in our lives?

The black-and-white stunner, which screened at the 2013 Hamptons International Film Festival under the title Oh Boy, opens Friday at the Landmark Sunshine in New York, with more cities to follow. We caught up with Gerster in a recent phone call to Berlin, where he talked about Germany’s tumultuous brand of history, movie title changes, and the at-times intimidating discomfort that can accompany early success.

Jan Ole Gerster, director of A Coffee in Berlin, courtesy of Music Box Films

With your feature film debut, you already won six 2013 German Film Academy Awards, including Outstanding Feature Film, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Screenplay. How does that make you feel, with your first film out of the gate?

Jan Ole Gerster: Being back in Berlin after traveling almost two years [with the film], I have a little bit of distance now, and I have a little more perspective. But when I was in the middle of it, it was a crazy experience, because I don’t know if you can imagine… When you do your first film, you dream about success, and you hope that it will find an audience, and that people will like it, or at least appreciate what you did. And then it turned out to be better than I ever thought possible, and I really never expected it to be like this.

I was at the European Film Awards next to Pedro Almodovar, and Ennio Morricone. Can you imagine? And my motley crew and I from Berlin–we were students who made a black-and-white film. It was a trip! It was wild. Sometimes when I think about it, I’m happy, but also a bit sad, because who knows if it will ever happen again, you know? That makes me sit down these days and work on my new project. [laughs]

As the writer/director, where did the story come from? Though set very specifically in Berlin, it explores some very universal themes–most prominently, the slacker young man who can’t seem to jumpstart his life. Were you a “Niko” yourself, or did you see him around you?

Jan Ole Gerster: I went to film school, and I wasn’t a big fan of film school, because I don’t go together so well with school. I wanted to study there, but I hated it at the same time, because it was so dry, and there were people trying to teach you how to write, blah, blah, blah. But there was one thing that one teacher kept telling me: “If you want to be unique, you have to express something personal–that’s the only chance you have to be unique.” It was like this phrase was chasing me for some reason; I thought he was right, but I had no idea how to do it. I thought, “My life is boring. Nothing is happening. I don’t know where I’m headed. How am I supposed to make a film about this? No one will ever see that film…”

At one point, I was so desperate with the script I was writing—something out of a textbook, or a screenwriter’s manual: How to Write a Screenplay in 10 Days, Go To Hollywood, Become a Millionaire—these books that really traumatized me, in a way. So I sat down and thought, okay, maybe I should give it a try, write about what’s going on in my life, what’s going on in front of my door, the encounters I have with people around me… to try to express this feeling of being lost. I knew the only way to make it a film worth seeing was to put some irony into it too–have an ironic point-of-view of somebody who is generating problems out of having no problems. He’s bringing it on himself.

I was always in love with anti-heroes, and the guy in my film is more identified with these kinds of people than with superheroes. So I sat down and wrote the first draft of A Coffee in Berlin—sorry, I have to get used to the new title!

Yeah, why did the title change?

Jan Ole Gerster: The film has now been released in more than 30 countries, and wherever we go, people say the film has to say “Berlin” on the posters for people to go to see it. I don’t know why—maybe because…

Because Americans are not so bright, and we need to be told explicitly [laughs]?

Jan Ole Gerster: No, it’s everywhere! In France, they changed the title; in Italy, they changed the title; and it always has something now about Berlin. I have to admit, after being out at festivals with the film, we could have picked a better title. So I just have to get used to it: A Coffee in Berlin. It’s a creative masterpiece. [laughs]

Courtesty of Music Box Films

Jan Ole Gerster: I think that’s why it somehow sneaks into film, because it’s not necessarily a statement about the Germans 70 years ago; it’s about the fact that even today, a generation that doesn’t have anything to do with that war still has to deal with the identity of being German. The film is about a young guy trying to find his way of life, or his identity, and I feel like I wanted to say something about Germans nowadays still trying to find their identity.

Because you never see any film coming from Germany that shows this ghost of the history in a film that’s set in the present, and how these ghosts are still a part of everyday life. They’re not dominating everyday life, but they’re around, especially in a city like Berlin.

I couldn’t tell why [these references] were important to me, but it felt right, and it felt necessary. Probably because at that time, I was thinking about a lot what it still means to be German these days—traveling to other countries: “Hey, where you from? I’m from Tel Aviv!” “Hey, I’m Jan, I’m from Germany.” People still have a reaction to that. So it still affects me, as someone who’s living in this country now, 70 years after the war.

Julika Hoffmann (Friederike Kempter) in A Coffee in Berlin, courtesy of Music Box FilmsWhere did you grow up?

Jan Ole Gerster: I grew up in West Germany, but it was very provincial, in the countryside. A very boring place. [laughs]

I lived in West Germany from 1977-1980, when I was a child. My father was at Ramstein Air Force Base, near Kaiserslautern. We actually drove to Berlin from West Germany, in our orange Volkswagen van. And we got to go into East Berlin; it’s a very vivid memory for me. But I haven’t been back since—everyone raves about Berlin, and I’m dying to go.

Jan Ole Gerster: When the wall came down, our parents took us to East Berlin that summer, and all I remember was this special kind of grey.

That’s what I remember, actually. It was grey and lifeless.

Jan Ole Gerster: Well, you can’t imagine—the wall came down 25 years ago, and it has totally changed. I am actually researching a lot of this footage right now for a new project. I’m spending hours and hours on YouTube, watching video of that time, and wow. Even though it seems to be so far away, it’s not. It’s weird that this all happened only 25 years ago; you can’t really recognize the city anymore.

When I moved to Berlin in the year 2000, people told me that I was already too late; the party was over. The first 10 years after the wall came down, this was an adventure park: people moved to East Berlin and lived in buildings for free because nobody was in charge anymore. The country that owned the buildings did not exist anymore, so nobody was responsible. So it all turned into this wild mix of rotting old buildings, new socialist architecture, graffiti all over the place, clubs, bars, studios, concert halls… I think the 90s were a wild decade for East Berlin.

But I still got some of the old taste, and now I keep telling the young people who move to Berlin the same thing—I probably sound like an old man…

I moved to NYC in the 90s, and that’s when the East Village was like that; now there are boutiques and fancy cocktail bars. It’s still a little grimy in parts, but nothing like it was 20 years ago.

Jan Ole Gerster: I know. I wish I could have been there, especially in the Andy Warhol and Velvet Underground years…

Tell me about your decision to shoot the film in black and white, which is stunningly beautiful. Was that always the plan? What did you hope it would achieve? Did you want to bring some of that old Berlin back into the picture?

Jan Ole Gerster: I think the idea was a little bit about giving more of a timeless feel to the picture. And because I felt that the film is about everyday life, black-and-white is very helpful to create a different perspective; different things come to the foreground. I feel like there’s a different kind of truth to black-and-white images than in films in color. This was something that I decided, I think, with the first page of the screenplay.

Matze (Marc Hosemann) and Niko Fischer (Tom Schilling) in A Coffee in Berlin, courtesy of Music Box Films

You said you are working on a new project. What’s next?

Jan Ole Gerster: I have two projects going on. One has to do with the neighborhood I live in, but on the night when the wall came down. It’s amazing how many stories are out there, when you start to talk to people. So this is in my head right now, and I’m writing a script about that. And the other one is a love story; Germany needs more love stories. [laughs]

Well, thank you very much, and I think everyone who sees the movie will want to head straight to Berlin.

Jan Ole Gerster: Yes! And you should do yourself a favor: don’t come in winter. Come in summer. Because even though sometimes I am fed up with Berlin, and I fantasize about living somewhere else, right now, it’s super hot and sunny, and it’s a really nice city to live in. Come visit!

A Coffee In Berlin opens Friday, June 13, at the Landmark Sunshine in New York, with more cities to follow.

This interview first appeared on The Huffington Post.